Are League of Legends Skins Pay-To-Win?

I wanted to test if premium skins actually improve your performance - or if they’re only cosmetic as Riot claims. Using data analysis, I broke down the numbers to find out. Along the journey, I reverse engineered the game's replay format and network protocol to collect the data.

I even created a simple website to showcase the results: https://LeagueOfWhales.com.

Introduction

Are League of Legends skins purely cosmetic, or do they provide subtle advantages that can impact gameplay? This question intrigued me, especially since over the summer, Riot released a $500 Ahri skin, and after Arcane Season 2, Riot released a $250 Jinx skin.

Since Riot’s official API doesn’t expose this data, I embarked on a technical journey to uncover the truth. This blog covers the reverse engineering process I used to extract and analyze the data, the challenges I faced, and the results I found.

Technical Analysis

Data Collection Challenges

To analyze the impact of skins on gameplay, I needed access to detailed match data, including which skins were used in each game. Since Riot’s API doesn’t provide this information, I had two options:

- Convince tons of players to use a third-party app (e.g., Overwolf).

- Download replay files and extract the data myself.

I chose the second option because it was technically challenging and novel.

Network Sniffing

To access replay files, I first needed to reverse engineer the internal LoL API. This required understanding the authorization flow and how replay download requests work. Network sniffing techniques isn't the goal of this post, so I won't go too deep into the actuals of how to get basic network traffic. The easiest approach is usually using Fiddler and forcing the target application, i.e. LeagueClient.exe, to use Fiddler as a proxy and accept the certificate that Fiddler uses. If that doesn't work, Wireshark is also another great app in a reverse engineer's toolkit. This is where some reverse engineering knowledge may be required. If you are new to reverse engineering networks, download Fiddler and follow some tutorials on it.

General Tools and Techniques

- Fiddler: Used as a proxy to capture HTTP(S) traffic.

- Wireshark: For deeper packet inspection.

After sniffing is enabled on the client, I can inspect the authorization flow. The first endpoint sends the username/password to the server, with some custom headers. At first glance, this seems easy enough to reproduce, but Riot has done a lot of work on preventing this to thwart bots, so the network request needs to mimic the client as close as possible - i.e., it needs to be HTTP2, with specific request headers, otherwise Cloudflare will reject the request. They also recently added a captcha service on top of it to further prevent bots. So, I had to make it look identical to the client to get it working. A lot of this was trial and error until Cloudflare said success. It would also be fairly trivial to just re-use the token that the client uses, but that's not as fun and then requires you to have a sniffed client running to get the token. It expires after a month IIRC (I use jwt.io to inspect tokens, it is very helpful, though Visual Studio now also has a built-in jwt decoder).

With this basic auth endpoint working, there's another service token needed to access the replay service - this can be seen in the network dump every 5 minutes. The token expires every 5 minutes, so we need to be sure to refresh the token during our replay download to refresh every 5 minutes as well. Nothing is too complicated about this request, pretty straightforward if you understand oauth and other auth flows.

Now when clicking download replay, we can see the replay download request - the response is just a http forward to the AWS S3 where it's located with the correct signing. Easy enough to reproduce, the main gotcha here would be the underlying http client you use and how to handle http forward requests.

🗒️NOTE: You can specify any match id, to download any replay file, including practice tool and custom games!

Pro teams could do this to see their competitor's secret strats, but according to Riot/HackerOne, it is not a security/privacy vulnerability. Which is weird because Riot has stated they care about privacy when it comes to custom games.

Also, when making the replay request, you can specify a lot of different strings to append to the redirect url, and it will respond with signed material. I couldn't find an exploit here and it's not a big attack surface, but still interesting.

The above key steps can be simplified to:

- Capture the login flow to mimic the client’s authentication process.

- Handle Riot’s anti-bot protections, including HTTP/2 headers and CAPTCHA challenges.

- Refresh service tokens to maintain access to the replay service.

- Reproduce the replay download request, which involves HTTP redirects to AWS S3.

Bandwidth Optimization

Another task I spent time on was optimizing this download - each replay is big, longer games are 20MB+. In the spirit of not wasting bandwidth, I wanted to find a way to optimize this download, to not incur any additional costs on the host. I also know I only care about the loadscreen packets, which is early in the game replay, so I was able to close the connection and stop the download shortly after starting the request, since the relevant skin packets would be in the first couple of KB. Thankfully this works because there isn't some decryption/decompression algo that isn't block that requires the entire payload to be downloaded to inspect any of it - effectively allowing me to stream the replay but only the first couple of seconds of the game.

Analyzing Replay Files

Now that we have a programmatic way to download a ton of replay files by match id, the next problem is analyzing the replay files.

Decoding Replay Format

League of Legends replays are stored in .rofl files, a format that has been documented by the community (e.g., search "rofl parser" on GitHub). The replay file contains encrypted packets identical to those used in spectator mode.

Now that we have broken up the payload into all the encrypted packets, this is where the reverse engineering gets more involved - we can either go directly to the exe code, use heuristics to find the relevant packets, or a combination of both. I find it easy enough to start with the heuristics, then go to the exe code to do the heavy lifting.

Decrypting Packets

For skin data, in the load screen, we can expect 10 packets (1 for each player), and that can help us find the opcode. Checking all the packets in a rofl file, we can find a specific opcode sent 10 times in succession, so we can infer that that's the correct opcode.

🗒️NOTE: 10+ years ago, I spent a ton of time researching League of Legends packets, during a time when Riot wasn't obfuscating the packets. There were even some developer groups that created private servers, some of us made a clientless leveling bot, and I did some unique things like used spectator mode to get exact times of when key objectives like dragon and baron were killed by the other team to give in-game advantages https://github.com/shalzuth/SpectatorClient. So I had some good tribal knowledge about the network protocol.

Knowing the opcode, we can go into the exe code to see the structure of the packet and how it's used, as well as the encryption of the packet. I am casually skipping over dumping the exe, since there's tons of other projects and people that have described this process. Generally, when exe's are packed, you have to figure out how to read the memory during runtime in a decrypted manner. Or, if the application is cross platform, you can use the executable binary from the Android/iOS/Mac version.

As we dive deep into the function, we see that there's specific patterns that detail the structure of the packet so we can find it in future patches of the game. We also see what offset the skin id is at. Understanding how the function works also helps in finding where it is in the exe bytecode in future patches to identify the opcode, versus using a packet capture to identify the opcode.

Knowing the offset, we can go to the decryption routine of the packet to be able to decrypt it. The packet encryption is just a simple series of bit magic for each field. The fields are packed and sequential, so you have to decode the entire struct This is a sample IDA decompilation showing the encryption / packing:

v8 = extractbits_7FF7A7FB3220(v7, 0LL, v6);

if ( v8 == 1 )

{

v9 = a1 + 16;

v10 = (_BYTE *)(a1 + 17);

*(_BYTE *)(a1 + 16) = 0;

if ( a1 + 16 != a1 + 17 )

{

do

{

v11 = __ROR1__(*(_BYTE *)v9, 6) ^ 0x9C;

*(_BYTE *)v9++ = -(char)(((v11 >> 1) & 0x55 | (2 * (v11 & 0xD5))) + 15) - 103;

}

while ( (_BYTE *)v9 != v10 );

}

}

else ( v8 == 2)

{

//snip for brevity

}

And this is how I converted it to C#, the master language (hot take, argue with me):

public static int ParseSkinId(byte[] packetPayload)

{

var offset = 7;

var p4s = new List<int> { 4, 7, 3, 6 };

var p4 = BitMath.extractBits(packetPayload, 0, 3);

if (p4s.Contains(p4)) offset++;

var p3 = BitMath.extractBits(packetPayload, 25, 2);

var champName = "";

if (p3 == 2)

{

var pp = packetPayload[offset];

var v31 = 0;

for (int i = 0; ; i += 7)

{

v31 |= (((byte)(BitMath.byte_7FF7A88A0EA0[((ulong)pp >> 2) | (byte)((byte)pp << 6)] + 75) ^ 0xA) & 0x7F) << i;

if ((char)(BitMath.byte_7FF7A88A0EA0[((ulong)pp >> 2) | (byte)((byte)pp << 6)] + 75) >= 0)

break;

}

offset++;

for (var i = 0; i < v31; i++)

{

var eof = packetPayload[offset + i];

var v28 = ((ulong)eof >> 2) | (byte)((byte)eof << 6);

var letter = (BitMath.byte_7FF7A88A0EA0[v28] + 75) ^ 0xA;

champName = (char)letter + champName;

}

offset += v31;

}

else if (p3 == 1)

{

//snip for brevity

}

else if (p3 == 0)

{

//snip for brevity

}

//Console.WriteLine(champName);

var skinKey = BitMath.extractBits(packetPayload, 15, 3);

if (skinKey == 6) return 1;

if (skinKey == 1) return 0;

if (skinKey == 5) return 2;

var p1s = new List<int> { 7, 4, 3, 2 };

var p1 = BitMath.extractBits(packetPayload, 44, 3);

if (!p1s.Contains(p1)) offset++;

var p2s = new List<int> { 5, 1, 2, 3 };

var p2 = BitMath.extractBits(packetPayload, 31, 3);

if (!p2s.Contains(p2)) offset++;

var skin = DecodeSkin(packetPayload, offset);

return skin;

}

public static int DecodeSkin(byte[] byteArray, int streamPos)

{

var result = 0;

var bitPos = 0;

var streamEnd = byteArray.Length;

if (streamPos >= streamEnd) return -1;

while (true)

{

var byteValue = byteArray[streamPos];

streamPos++;

var v7 = BitMath.__ROR1__(BitMath.__ROR1__(byteValue, 3), 1);

var v8 = BitMath.byte_7FF7A88A0EA0[((ulong)((byte)(v7 + 65) ^ 0x91u) >> 1) & 0x55 | (byte)(2 * (((v7 + 65) ^ 0x91) & 0xD5))];

result |= ((v8 >> 1) & 0x55 | (2 * (v8 & 0xD5)) & 0x7F) << bitPos;

var decodedByte = 88 - BitMath.__ROR1__((BitMath.__ROR1__(BitMath.byte_7FF7D262C300[byteValue], 7) - 57) ^ 109, 6);

if (decodedByte < 0x80) break;

bitPos += 7;

if (streamPos >= streamEnd) return -1;

}

return result;

}

I thought about a couple different ways to programmatically do this, and landed on creating an analyzer to dump out the order of operations. I really wanted to use Unicorn (emulator), but the decryption routine re-encrypts the packet in memory, and when the struct is used it gets re-decrypted, so using the emulator wouldn't work for this use-case. This lump of work is still a work in progress, intended to help translate those bitmagic instructions to C# code. It sometimes works, sometimes doesn't.

Frontend and Visualization

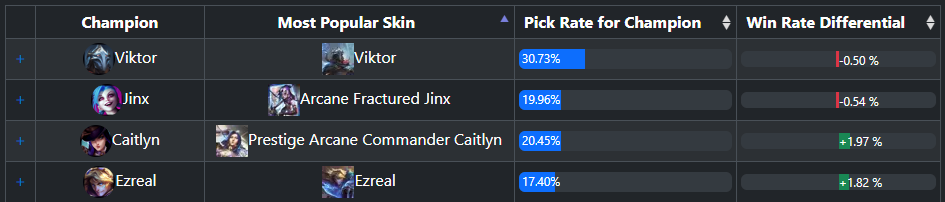

With the data collection in place, we can do all the normal statistics that you can think of. I am not an expert front-end developer, nor an expert statistician, so it might not be pretty nor have the most interesting results.

I created a small frontend, https://LeagueOfWhales.com, to display the output. Not too many gotcha's, the main one being skin id names and chroma color names aren't in the static data and are sometimes incorrect on the server side even. I also don't have great segmentation on the front-end of different ranks/roles/game modes/etc., all the games are just lumped together.

Results

Preliminary analysis suggests that some skins may have minor advantages. For example:

- The pricy $500/$250 skins do not impact performance in a significant way (+/- 0.5%)

- Skins with unique particle effects (e.g., iBlitzcrank) can make abilities harder to see and react to.

- Certain chromas might blend better with the environment, offering a subtle edge. However, more data and analysis are needed to draw definitive conclusions.

Future Project Ideas

I have some other cool ideas that use replays as a source of data:

- Jungle route tracker. This already exists on op.gg and some other sites, that use their massive user count to collect data when they run the app on their pc.

- Script detector. To do analysis like I did for skins, i.e. to see what % of players in Diamond are cheaters.

- Create a spectator service to convert a rofl to a spectator stream. And maybe even do funny things, like changing the size/skins of players, since the spectator stream isn't signed like the replay files.

- Do the same thing for TFT. I never really played TFT, so I don't know what cosmetics or skins there are, but I'd imagine there's less of a difference compared to LoL since it's not as fast/reactive. If I had infinite time, I'd do all 4.

If you’re interested in collaborating or have ideas for projects, feel free to reach out. And don’t forget to check out https://LeagueOfWhales.com to explore the data for yourself!